Rave Reviews from the Critics…

Debut 1941

“Monterone gripped the audience in the form of tall, 19-year-old Jerome Hines, Los Angeles bass. It was an auspicious debut and revealed a voice which not only carries through full chorus and orchestra but has an arresting musical quality.”

Los Angeles, 1941 Shirley Boyes

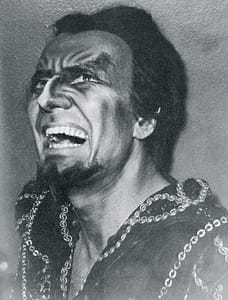

Méphistophélè

“Hines’ work as a singer and actor was remarkable for so young a man. In his 21 years he has accomplished more than many a veteran actor. The role of Méphistophélè is considered one of the most difficult for basses, but Mr. Hines carried it with the insight of a genius… The applause that greeted him was thunderous.”

The Tribune Sun, 1943 Frances Imgrund

the Wanderer

The forty-year-old Hines exudes freshness in voice and appearance, provided with a dash of whimsy. Without any strain, he delivered the never-ending second act saga in Die Walküre. Hotter, in contrast usually put more mystery and suspense into his interpretation. With Hines, the tale unfolds more gradually. Nonetheless, his performance sounded very good.

Bayreuth Ring, 1961 Rudiger Winter

A TriBute

Most of his discs derived from live performances. They reveal a sterling voice, a refined style, consisting of a burnished tone, a fine line and exemplary diction, although he never seems to have have been a very profound interpreter.

The Guardian, 2003 Alan Blyth

DETAILED BIOGRAPHY

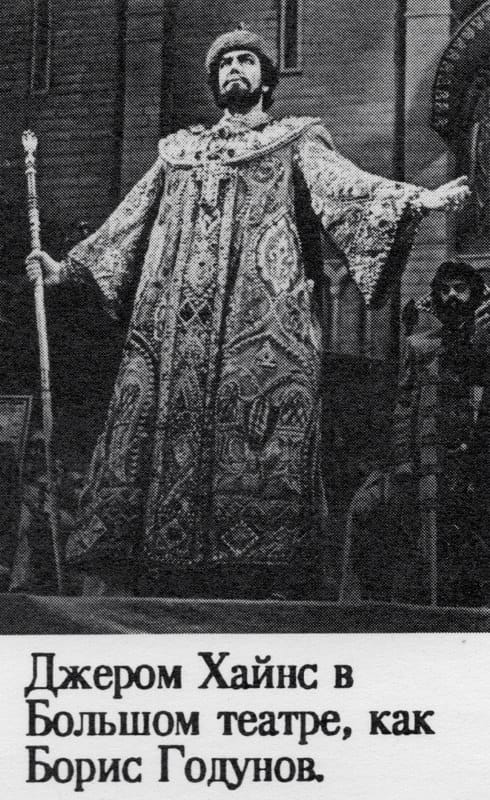

Jerome Hines was a well-known American opera bass, who was a beloved artist among the legendary icons of the Metropolitan Opera of New York City for many years. His height (6 feet 6-1/2 inches/2m), stage presence and stentorian voice made him ideal for such roles as Sarastro in The Magic Flute, Mephistopheles in Faust, Ramfis in Aida, the Grand Inquisitor and King Philip in Don Carlo, the title role of Boris Godunov and King Mark in Tristan und Isolde. In contrast, his talent, humor and vocal versatility also allowed him to sing Broadway hits, Negro Spirituals, and hymns of faith to thrill national audiences in the Golden Age of Television through The Voice of Firestone broadcasts.

First Steps

Hines was born Jerome Albert Link Heinz in Hollywood, California, on November 8, 1921. The young Hines was painfully shy, and discovered classical singing after his mother suggested lessons, thinking it might help him to become more extroverted. He had been kicked out of the junior high school glee club because his untrained singing was off-pitch. As his confidence grew, at the urging of his voice teacher, he threw himself into studying a diverse repertoire of art song and opera. Early private recordings of a 16-year-old in 1937 show the promise and voracious appetite for learning that developed into a phenomenal talent sought by opera houses on three continents for more than 50 years.

Hines was born Jerome Albert Link Heinz in Hollywood, California, on November 8, 1921. The young Hines was painfully shy, and discovered classical singing after his mother suggested lessons, thinking it might help him to become more extroverted. He had been kicked out of the junior high school glee club because his untrained singing was off-pitch. As his confidence grew, he threw himself into studying a diverse repertoire of art song and opera. Early private recordings of a 16-year-old in 1937 show the promise and voracious appetite for learning that developed into a phenomenal talent sought by opera houses on three continents for more than 50 years.

His intellectual was fine-tuned by the study of mathematics, and chemistry at the University of California, at Los Angeles, while also taking voice lessons. Eventually Hines made his opera debut at the San Francisco Opera in 1941, singing Monterone in Rigoletto. He also premiered an orchestral monologue written by America‘s pre-eminent black composer, William Grant Still, at the Hollywood Bowl. He changed his surname to Hines at the suggestion of his manager, Sol Hurok, to avoid the anti-German feelings prevalent during World War II.

In 1946, Hines made his debut at the old Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, as the Sergeant in Boris Godunov. He went on to sing forty-one consecutive seasons there and in the Lincoln Center location, longer than any other Met principal singer (until the 2008–09 season), encompassing 869 Met performances of 45 roles in 39 operas. During this time he pursued further voice studies with Samuel Margolis and Vladimir Rosing and began to devote the same disciplined pursuit of the theories and practices of classical vocal artistry that would allow him to sing well into his 70s and to teach aspiring vocal artists. The personal choices he retained and perfected throughout his career permitted him to adapt his unique, dark-timbred, voluminous voice to an unusually broad repertoire.

Unlike many of his colleagues that remained domestic “Met stars”, this American vocal phenomenon responded to the siren call of international stages that beckoned him. In 1953, Hines made his European debut with Glyndebourne Festival Opera as Nick Shadow at the Edinburgh Festival, in the first British performances of Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress. In 1958 he made his debut at La Scala in the title role of George Friedrich Handel’s Hercules. From 1958 to 1963, he sang the roles of Gurnemanz, King Mark and Wotan at Bayreuth in Wagner’s Ring Cycle. In 1961 he first appeared at Naples‘ Teatro San Carlo in the title role of Arrigo Boito’s Mefistofele.

While suffering with a cold, he ignited the stage in the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires with the famous confrontation duet of Verdi‘s Don Carlo with his European counterpart Hans Hotter.

In 1962 he sang Boris Godunov at the Bolshoi in Moscow, famously for Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev on the eve of the resolution of the Cuban Missile crisis. His description of his final performance of the run, and a sudden announcement that Khrushchev would sit in the private box next to the stage from which Hines hoped finally to make a film recording of his Boris performance, shows his humor and understanding of diplomatic couriers in this particular instance. Still in costume (that included 3-inch heels), he towered over the powerful leader—half his size—when he met him in an opera house reception room. When questioned whether all Californians were of similar stature, Hines quipped that he was a midget in comparison. In his words, “when I met Premier Nikita Khrushchev, he asked me how I could fall at the end and not get hurt, so I told him I took tumbling in college. He then turned to another man in the Politburo and asked if he could take a fall like that without hurting himself. After a momentary shiver, Krushchev continued, “Oh, no, don’t do that. You’re too important to matters of state.” The message he was asked to share with the American people of the leader‘s best intentions toward them was repeated verbatim, when he was met by the press on the tarmack of Idlewild Airport (now JFK) in New York. News of the meeting had preceded him. De-escalation of the Crisis soon followed.

Jerome Hines worked for authentic diction and style in the many languages used by composers of the works he performed. He was equally meticulous in approaching his roles and even learned alternate scores for a particular role, as with Boris Godunov. He sought to make his acting as realistic as the context of the character allowed. For instance, Mussorgsky wrote a heart attack as Boris‘ demise after his gripping monologue. Hines decided that a brain aneurysm might be better, given the erratic nature of the monarch and his merciless acts. It was convincing, but eventually vetoed by Rudolf Bing as too gruesome. Often, he would substitute God, or descriptions of faith in secular lyrics as a statement of his own belief. Happily, he was never sued.

Hines turned to teaching aspiring opera singers later in his career, founding the Opera–Music Theatre Institute of New Jersey in 1987. Through generous support of Governor Thomas H. Kean‘s education initiative he was able to bring such greats as Franco Corelli and Marilyn Horne on board to work with students in master classes. He continued performing virtually until the end of his life; among his last appearances was a concert performance as the Grand Inquisitor with the Boston Bel Canto Opera in 2001, at the age of 79. Hines recorded albums of sacred song, opera and other classical vocal music. Sadly, none are commercially available today. CAI hopes to change this in the future.

FAITH IMPACTS ART — I Am The Way

Hines’ mastery of the natural sciences, linguistics, classical vocal art and stagecraft were grounded in years of study. Composition and music theory were not among them. The idea for an opera on the life of Christ came to Jerome Hines years earlier, in 1950, when a pair of impresarios, who presented an annual Passion Play in Los Angeles, asked him if he knew of a composer that might write incidental music to the finale of their theater piece, in an effort to create renewed enthusiasm among attendees. Hines thought immediately of his friend Albert Hay Malotte, an American composer whose setting of The Lord’s Prayer is a beloved staple of that country`s sacred music. Malotte wasn’t interested in writing the finale, nor in Hines’ suggestion that he compose his own musical Passion Play. Neither man was probably familiar with Anton Rubinstein’s 1892 Christus, which the Russian composer called a “sacred opera” and was seen in only a few performances before being forgotten. Nonetheless, the concept of an opera on the adult life of Christ intrigued the amateur composer in Hines to the point that between engagements and the demands of a family that came later on, he began to plot out textually and musically how he might treat a subject so vast and so important. Believing his “sacred music drama” would be the only work in all of the operatic canon to do this became an additional challenge. The resulting work of more than ten scenes was written by someone never trained to do so.

Hines relates the intersection of this project with a silent dialogue inside himself as to why, given the level of professional and material success from his international career, and the joy of recently marrying his beloved wife, Lucia, he was compelled to move ahead. Most notably, by his own account, in the process of its composition, Hines` spiritual life shifted from nominal religious observance to a deep personal commitment of his life to Jesus Christ. The opera, I Am the Way, was presented as his personal testimony of faith—not an operatic world premiere—in a private non-theatrical location, New York City’s Salvation Army Centennial Memorial Temple on March 30, 1956 and featured three acts of two scenes.

The opera has always been privately produced, within the purview of Christian Arts, Incorporated, the non-profit corporation founded by Hines shortly after the premiere, to be the custodian of the opera and the producer of complementary educational workshops and performance opportunities for young artists. Once his focus turned to a man unique in the history of the world, many familiar structures laced the melodies, the dense orchestration that underpinned the gravitas of the subject matter, and full dramatic voices necessary to perform it. Hines sang the role of the Christ in nearly 100 performances, until 1997, at age 75. Frankly, the work was never intended to be published for worldwide distribution or productions outside of CAI auspices. All cast members, down to comprimario roles, were selected only by Hines and the corporation’s artistic director, Derek De Cambra, whose staging accompanied the work from 1958 until his death in 2009. Hines died of undisclosed causes in 2003, at age 81 at a Manhattan hospital. Jerome Hines was married to the soprano Lucia Evangelista from 1952 until her death from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 2000. They had four children, David, Andrew, John and Russell.

Frankly, no one who ever spent time around Jerome Hines was not asked at some point whether the person had considered the question of faith in Jesus Christ as a life decision. He took very seriously, the roles he sang, or things he was asked to do onstage. Often, he would substitute God, or descriptions of faith in secular lyrics as a statement of his belief. Happily, he was never sued. More about this aspect of his life here…

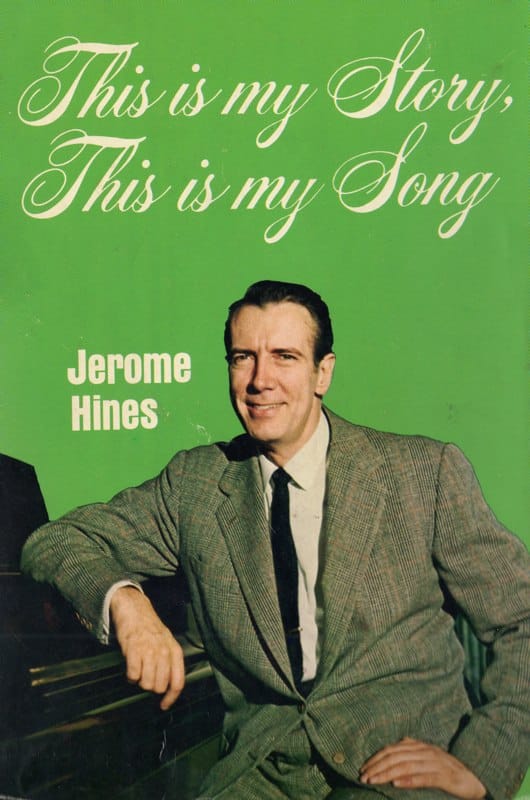

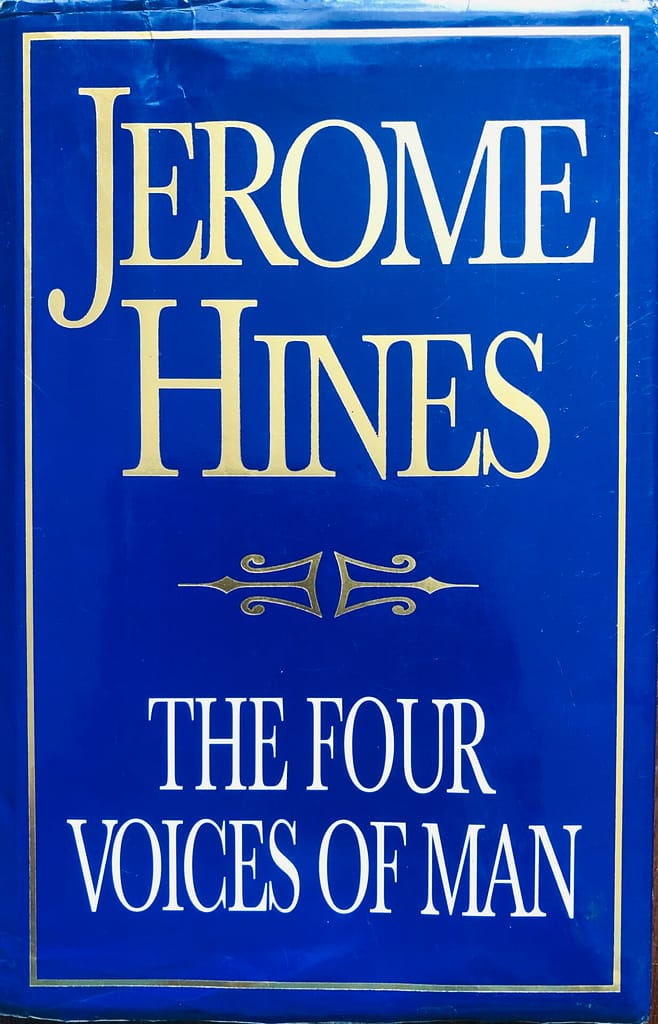

PUBLISHED AUTHOR

Hines authored several books. One a memoir, and two others on classical vocal art technique.

This is My Song (1969) ISBN 0-8007-0313

The Four Voices of Man (1997) ISBN 0-87910-025-

Great Singers on Great Singing (1981) ISBN 0-87910-099-0

Academic Articles by Hines contributed to Mathematics Magazine*(courtesy of Wikipedia):

1951: “On approximating the roots of an equation by iteration”, Mathematics Magazine 24(3):123–7 MR1570498

1952: “Foundations of Operator Theory”, Mathematics Magazine 25:251–61 MR0047101

1955: “Operator Theory II”, Mathematics Magazine 28(4):199–207 MR1570730

1955: “Operator Theory III”, Mathematics Magazine 29(2):69–76 MR1570767